Facing persecution in Myanmar, some Rohingya people have left for the United States, where many are finding new homes—and new challenges—in the Midwest.

The Rogers Park neighborhood on Chicago's North Side is home to about 400 Rohingya families, one of the largest concentrations in the country. Ninety miles north in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, there are about 5,000 Burmese refugees, including about 600 Rohingya families (the others are Karen and Chin). Burmese people make up Wisconsin's largest refugee population; they are the second largest refugee population in Illinois.

The two cities face similar refugee resettlement issues, but members of the Rohingya communities feel they're handling them differently. Refugees in Chicago receive assistance and feel a strong sense of community, while those in Milwaukee feel left on their own. Residents in Milwaukee are trying to assist each other, but without government support like that received in Chicago, it's more difficult for the community to thrive. The Rohingya refugees in Chicago feel hopeful that they can integrate into American society, find jobs, learn English, and raise their families in a safe community with economic opportunity, while the attitude in Milwaukee is more somber.

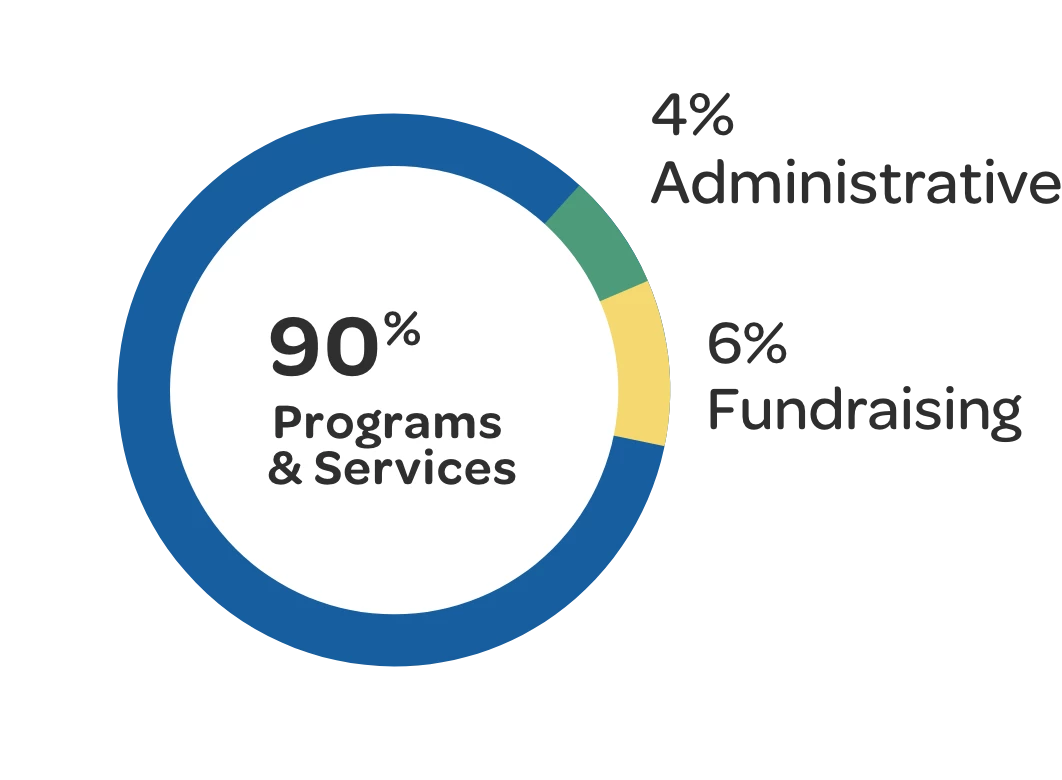

In Chicago, the Rohingya Community Center is thriving, thanks in large part to funding from the Zakat Foundation, an Islamic-American apolitical, non-profit organization. The center was started in 2016 by Nasir Zakaria. A Rohingya refugee who in 2013 moved to the U.S. from Malaysia, Zakaria taught himself English while working as a dishwasher at the Rivers Casino. The center teaches English and helps children with their homework, walks people through resettlement paperwork, provides translation services, assists with medical issues, and more.

The Zakat Foundation's reach also extends outside of the U.S. It maintains international offices in Jordan, Turkey, Mali, and Bangladesh, and works with partner organizations around the world. Since its creation, the Rohingya Cultural Center has raised and distributed $71,000 to villages in Myanmar for food and medicine. Aside from its social services, it also helps fulfill the emotional needs of the Rohingya community in Chicago. "We are becoming a place to put down roots and share stories in the Rohingya language with friends who truly understand the struggles we have faced," Zakaria says.

Like Zakaria, most refugees in Chicago and Milwaukee left Myanmar in the 1990s and lived in Malaysia for years before they had the opportunity to come to the U.S. Rohingya are not recognized as citizens in Myanmar, and are subjected to limited rights in Malaysia.

In Milwaukee, Mohamad Anuwar and Abdul Hamid, Burmese refugees and interpreters at Aurora St. Luke's Medical Center, are taking inspiration from Zakaria to start their own center in lieu of government support.

"I was born in Burma, I lived there, I attended school there, I finished my bachelor's degree there, I speak the language, but still I am not a citizen of that country," says Anuwar, who has lived in Milwaukee since 2015. Before working for St. Luke's Medical Center he worked for the United Nations in Malaysia.

Hamid and Anuwar are working to build their own version of Chicago's cultural center in Milwaukee. The center, the Burmese Rohingya Community of Wisconsin, will provide Rohingya refugees with interpretation services, home and health-care assistance, new arrival paperwork assistance, workforce development tools, English as a Second Language classes, food stamps, and more. They hope they can provide refugees in Wisconsin a better life than in their home country.

"We were refugees within our own country," says Abdul Hamid, another interpreter at Aurora, and former president of the Rohingya Society of Malaysia.

Currently, refugees in Milwaukee can turn to the Rohingya American Society and the adjoining mosque, which provides English and religious classes to children, but little else.

In both Illinois and Wisconsin, politicians—particularly Democrats—have made refugee assistance a priority, at least in rhetoric. Representative Gwen Moore (D), whose district covers Milwaukee, was photographed on the front page of Roll Callholding a sign reading "Refugees Welcome." Moore has written letters to Secretary of State Rex Tillerson calling on him to "take concrete actions in response to the unfolding humanitarian crisis in Rakhine State," and urging him to "do everything possible to ensure protection and security for those trapped inside Burma."

On a city level though, Rohingya in Milwaukee don't see the government taking a lead.

"So far we haven't seen any programs from the city," Anuwar says. "Refugees get some assistance from refugee agencies, but the city is not [directly] involved with the refugee community here."

Chicago residents are more optimistic, partly because Senator Dick Durbin (D) and Representative Jan Schakowsky (D), whose district encompasses the Rogers Park neighborhood, have engaged with them. The representatives recently took a trip to Myanmar. There they met with government officials, Rohingya communities, and international organizations working in the region. They also visited refugee camps in Bangladesh to determine how international action could best help bring an end to violence and displacement.

We are talking about the largest group of stateless people in the entire world right now," Schakowsky said at a recent press conference at the Rohingya Cultural Center. "We saw the worst human rights abuse now taking place on the face of planet Earth," Durbin said.

During the press conference, he and Schakowsky recounted stories from women they'd met in Bangladesh who had seen their husbands, brothers, and children killed before their eyes. Refugees were invited to speak, each tearing up as they talked about leaving Myanmar years ago, or told stories about family in camps still trapped in the country.

We are begging the world to save our mothers and sisters back in Burma," said one woman. "I am asking the U.S. We don't have anyone else. I am not able to eat or sleep because of the situation back in Burma. I'm begging the U.S. to save our community."

Rohingya in Chicago feel re-assured their city's government is on their side because of Durbin and Schakowsky's presence both in Myanmar, and in Chicago itself.

Rohingya in Chicago mostly work in low-wage janitorial or airport jobs, sending money to relatives in Myanmar whenever possible. Though their lives in Chicago are still difficult, they see hope for their children. Dozens of children show up each night for English classes at the Rohingya Cultural Center, which also helps with standardized test prep. Zakaria says his goal is to help Rohingya refugee children become doctors or lawyers, so they can, in turn, help other people. The center also offers English classes and job readiness workshops for adults, and has partnered with DePaul University and the University of Illinois–Chicago to develop mental-health counseling for refugees. The center's resources come from donations, not the government, but being vocal about refugee issues has endeared Durbin (D) to the Rohingya community.

We are so happy here for the government," Zakaria says. "Durbin comes to our center, he visits us, he is working to help us."

It's not only face time that counts. On a federal level, Durbin laid out actions he's working toward to help Rohingya both in Chicago and abroad. These actions include: fighting for greater access for non-governmental organizations and media in the Rakhine State; holding members of the Myanmar military responsible in a court of international law; partaking in repatriation efforts, monitored by the United Nations High Commission on Refugees; closing prison camps within Myanmar; and working to give Rohingya people in Myanmar the right to vote.

"The responsibility of our government must include assistance to the Rohingya people," Durbin says. "I am going to work to provide resources for assistance around the world, especially when it comes to the Rohingya people in Bangladesh."

We are on your side," says Schakowsky, who has also met with Milwaukee residents, though they live outside of her jurisdiction.

Still, Milwaukee Rohingya are grateful for the opportunities granted them in the U.S. "Here, people feel safe, secure, and happy because they have food and shelter, and especially education for their kids. That's something we cannot even get in Malaysia," Hamid says.

They are also utilizing a freedom that's relatively new: the right to protest. A rally in Milwaukee in September of 2017 held to bring attention to human rights abuses in Myanmar drew more than 150 people. "It is good to increase awareness through demonstrations," Anuwar says. "Many Americans don't know what's going on in Burma, or who the Rohingya in their own community are."

The Rohingya Cultural Center has held five demonstrations in the 18 months it's been open, including two in downtown Chicago. Rohingya also joined demonstrations in New York and Washington, D.C., to protest the travel ban last year. Local protests mainly raise awareness of the atrocities happening within Myanmar, and are meant to urge the U.S. government to do more for people hoping to reunite with their families.

Chicago's politicians are working toward developing solutions in Myanmar and bringing more refugees to the U.S. Grassroots action, for now, supplements more formal support in Milwaukee.

While the two cities have handled the Rohingya populations differently, refugees in both cities agree on one main point: They are urging the federal government to take a stronger stance on promoting democracy in Myanmar, noting that until genocide stops in their home country, they cannot be completely at peace.