Posted by HUMERA LODHI on March 31, 2021 05:00 AM. Retrieved from www.kansascity.com.

Seventeen-year-old Ronnie Amiyn banged on the front door of a house and called for help.

He had been shot in the face, and blood rushed down his cheek. But the house was not his home, and the people inside turned him away. So he ran through the streets north of Delmar Boulevard in St. Louis, using his hand to stanch the bleeding and frantically crying out to strangers.

He remembered how the stranger who shot him had laughed as he ran away. And how his friend had left him to die, escaping in a car.

“It turned my heart black in that moment,” Amiyn says now, at age 46. “I’m like, ‘that’s it, I’m not caring about anyone anymore.’”

Soon, Amiyn would start carrying guns himself and wind up in prison.

Poverty and guns together scarred Amiyn with childhood trauma and changed the trajectory of his life, he believes. There had been times in his youth when he was neglected: Christmas went by without any presents. It was not uncommon to be left at home with nothing to eat. There was no money in the house.

Amiyn grew up close to one of Missouri’s main centers of poverty and gun violence. St. Louis City, with 266 homicides last year, has the highest rate of gun deaths in the state.

And the metropolitan area is home to three of Missouri’s 10 poorest ZIP codes: 63106 in St. Louis City, 63140 in Kinloch, and 63133 in Pagedale. All three are at least 60% Black.

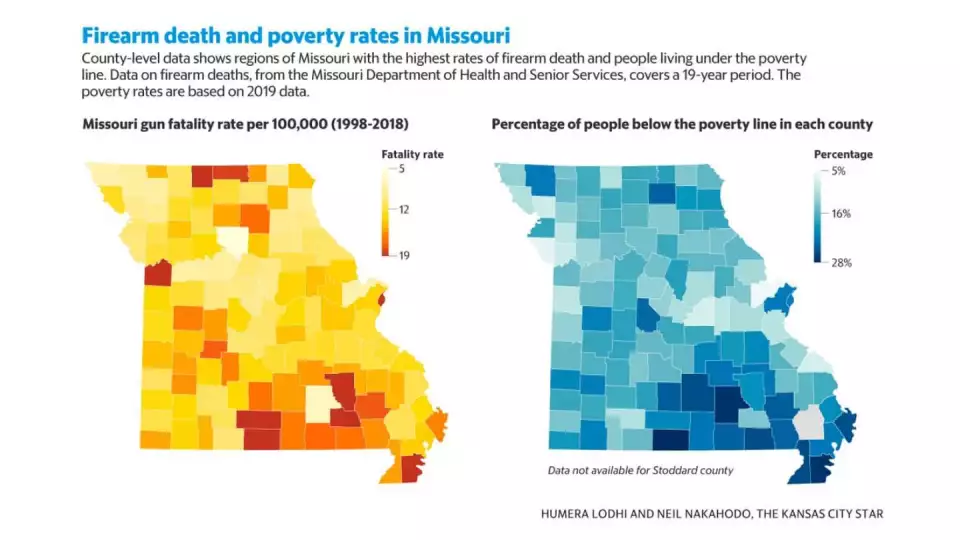

To understand how problems of income and economic mobility drive gun violence in Missouri, The Star examined state health department data and census figures that showed where rates of gun deaths and poverty were highest.

The newspaper found some of the highest rates of both in two regions: St. Louis City, certain parts of St. Louis County, and the rural southeastern counties of Reynolds, Pemiscot, Wayne and Carter.

Public health experts, gun violence researchers and residents of the hardest-hit communities say income — or the lack of it — is one of the key factors that determine how likely a person is to be a victim or a participant in gun violence. Other factors include having stable and secure housing, access to enough good food, attending quality schools, and growing up in racially segregated or economically depressed neighborhoods.

The connection between poverty and violence is “strong and has been consistently documented,” said Julia Schleimer, a data analyst with the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of California, Davis.

Poverty works on multiple levels to make someone more likely to experience gun violence, Schleimer said. For instance, high-poverty neighborhoods might not have quality educational opportunities to set kids up to succeed in the job market, and physical features, like abandoned buildings, can be more conducive to violence.

Conditions that lead to extremes of poverty and gun violence in St. Louis, as elsewhere, are a product of historical, structural racism, said Serena Muhammad, director of strategic initiatives at the St. Louis Mental Health Board.

That is what drives the disinvestment you see,” she said. “It’s not accidental, people didn’t just wake up in a disinvested neighborhood, it happens over time.”

Black Missourians are twice as likely to live in poverty compared to their white counterparts, according to the Center for American Progress. And research from the Violence Policy Center in Washington, D.C. shows they die from homicide at more than nine times the average rate for the general U.S. population, far outpacing every other state.

Revitalizing communities and making people feel safe requires money. This year, St. Louis is expected to receive $500 million in coronavirus relief funding to be overseen by the next mayor.

That figure, which is tied to poverty and unemployment rates, as well as housing needs, is five times what the average community across the country will receive. Kansas City will receive the next highest amount in Missouri, with $195 million.

After a year that saw historic levels of gun violence, it is clear that seeking better outcomes will take asking hard questions and looking for solutions that work, said Daniel Isom, former chief of the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department.

“Concentrated poverty and disadvantage in Black and brown communities led to a particularly intense cycle of violence,” Isom said. “It’s really about ensuring the personal safety of young men of color — we never look at it that way.

“To begin to ensure their safety, we have to look at ourselves, and hold ourselves accountable and say: Are we actually giving everybody an opportunity to have quality jobs and a fair shot to have quality income?”

LIFE ON NORTH GRAND

When worshipers gather for Friday prayers at a mosque on North Grand Boulevard, among them are people who have been shot and people who have shot someone before.

Even the man leading the prayers at the Al-Mu’minun Islamic Center has been touched by the violence. The scariest moment of Imam Jihad Mu’Min’s life, he says, was when he thought his son had died.

“I’ve lost my mother, I’ve lost my father, I’ve lost sisters, I’ve lost brothers, and I was hurt by that, but it wasn’t like that brief instance when I thought my son was killed,” Mu’Min said. “It’s unnatural for a parent to bury a child.”

His son, a teenager, was at a park when a stranger started an argument and shot him. One of his lungs collapsed, but he survived. The assailant was never charged.

Mu’Min is not sure it would have made a difference in his community’s future even if someone had been arrested.

He sees devastation all around him. Community centers have shut down, shops have shuttered, and many of the city’s historically Black high schools have closed.

His ZIP code, 63106, bordered by North Grand and Delmar boulevards, is the fifth poorest in Missouri and almost entirely Black. The average income is about $16,000 per year.

North Grand Boulevard touches three of St. Louis’ 20 neighborhoods that accounted for more than 25% of all homicides in Missouri in 2019, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Delmar is a dividing line between the predominantly Black and white sections of the city. Three of Missouri’s five wealthiest ZIP codes are just a short drive away in the mostly-white suburbs of St. Louis City: Chesterfield, Ladue, Town and Country, and Frontenac.

“It’s night and day, Mu’Min said. “They leave abandoned buildings, trash, and vacant lots here, and then you go on the South side of the city, and it’s just immaculate. It just makes me feel like we’re being neglected. It’s almost deliberately just sitting back and letting the community implode.”

Mu’Min sees the pain in the faces of the community members he mentors.

“For the people who witness that, it puts them in a mind frame that no one cares,” Mu’Min said. “It gets them to the point where they’re hopeless. They’re just like, ‘we don’t have anything to live for anyway,’ so here comes the violence, here comes that not caring about living a life or taking a life.”

At the mosque, staff collect money each week to try and help senior members of the community pay their bills. And on a near-weekly basis, the mosque has been working with other local and national organizations to hand out food packages to those in need during the pandemic. They started by making 800 boxes packed with staple foods like bread, milk, and eggs.

Almost every weekend, they run out of boxes to give.

Mu’Min, 63, has lived in St. Louis nearly all his life.

“It did not used to look like this,” he said. “You had so many different programs and resources in communities at one time.”

Black-owned businesses once dotted the street. More people in the neighborhood owned their own homes, and fewer carried guns. Schools were within walking distance, and government-funded community centers were thriving with lively events.

Losing some of those things had consequences in the lives of residents. Many who work in gun violence prevention say poverty contributes to a sense of hopelessness and a feeling of not having control over one’s own life. Desperation can lead some to consider violence an option.

Mu’Min has seen it in his work as a prison chaplain, counseling men convicted of firearm charges.

“The big majority of them, they didn’t set out one day and say, ‘Well, I’m going to go out and commit a murder,’” Mu’Min said.

“Overwhelmingly, these were young men, who didn’t have a job, weren’t in school, and had no type of community program that we used to have to help ourselves.”

The same is true of both the victims and the offenders, the imam said, pointing to one of the worshipers at the mosque: Ronnie Amiyn.

‘CAST OFF’

A year after he was shot, Amiyn participated in an armed robbery and sexual assault.

He and a partner held a young couple at gunpoint, forced them to remove their clothes and stole their money. Amiyn also sexually assaulted the woman, and his partner shot the man when he tried to defend her.

Amiyn pleaded guilty to the shooting, the robbery, and the sexual assault, and at age 19 was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

“I do want to say I’m sorry, to express remorse for the actions that led up to their pain and distress,” Amiyn said. He would like to reach out to the victims to apologize, he said, but he is afraid the contact could further victimize them.

“I don’t want that,” he said. “But I do want the opportunity to say I’m sorry.”

In prison, Amiyn converted to Islam, changed his name and became an imam for incarcerated Muslims.

“There were actual individuals there who were sentenced to life in prison, never going home,” Amiyn said. “But they were transformed and they spent their time and energy working to mentor young guys coming through the system.

“I’m so grateful because they taught me Islam and they taught me how to be a man. I needed a role model and I needed guidance and I actually got it from people that society casts off as irredeemable.”

In 2018, after serving 25 years, he was released on parole.

Like many people leaving Missouri prisons, Amiyn came out poorer than he went in. After years of working for, at most, $31 per month, returning citizens are given bus tickets to the neighborhoods they were living in when they committed their original offense.

“My finances were zero,” Amiyn said. “For myself, personally, I knew I wouldn’t reoffend again, but I was worried about the suffering.”

At the Medium Security Institution in St. Louis, more commonly known as the workhouse, warden Jeffrey Carson has seen how a lack of economic mobility creates a cycle of incarceration.

He’s seen people leave the jail only to come back almost immediately because they had nothing on the outside. He’s seen fathers and sons in jail at the same time. He remembers a man who was in jail for more than a year for stealing some bread.

Between 2010 and 2019, the recidivism rate for all Missouri offenders was over 40%, Carson said.

Amiyn’s new outlook on life helped keep him from going back. He took classes at a community center, got certified as a carpenter, and started a job as a housing coordinator for Criminal Justice Ministry, an organization that provides reentry programs.

Both Amiyn’s parents eventually overcame struggles with substance abuse that shaped their household in his childhood. He is now close to both of them, particularly his mother, who he sees as having raised him as best she could, even without sufficient support and resources.

“Man, I feel for the kids of today,” Amiyn said. “I don’t believe our communities are regarded like other communities are. When someone from another demographic commits a crime the initial response is, ‘Oh, poor kid, I wonder what made him do that.

“But for another demographic, they are ‘monsters’ that need to be treated with the harshest punishment.”

DELIVERING RESOURCES

Reducing gun violence is going to take policy change and large scale reinvestment in communities that were intentionally ignored for decades, said Ari Davis, a senior policy analyst at the nonprofit Coalition to Stop Gun Violence.

In North St. Louis, the nonprofit Better Family Life is seeking to redevelop Hamilton Heights, a largely Black neighborhood where almost all residents are living below the poverty line.

To bring residents into the neighborhood and keep them from leaving, the organization seeks to build new housing, help people buy homes, and get people resources to help them stay. The group is also working to prevent people from being evicted.

“We have families that are attempting to raise children in an environment that is hostile even just to existing,” said Tyrone Turner, vice president of housing and asset development at Better Family Life.

“The solution is intense resource delivery in the neighborhood.”

To get resources where they are most needed, policy makers and community leaders also see potential in programs that put cash in the hands of individuals.

Researchers in California two years ago launched an experimental program that provided residents $500 per month. In the end, leaders of the Stockton Income Experiment said results showed the best way to get people out of poverty was simply to give them more resources.

The idea is being carried forward by a group of city leaders across the country under the banner of Mayors for a Guaranteed Income.

Liberal politicians like New York City mayoral candidate Andrew Yang have called for a so-called universal basic income, essentially a government stipend intended to alleviate household economic pressures.

In addition to stimulus checks for most Americans, the latest coronavirus bill includes direct monthly cash payments to parents of children. The bill, signed into law by President Joe Biden earlier this month, is anticipated to cut the nation’s poverty rate significantly.

Both candidates for St. Louis mayor, city Treasurer Tishaura Jones and Alderman Cara Spencer say they would spend COVID relief funds on housing assistance, homeless services, workforce development plans, and help for small businesses.

Jones’ campaign has also indicated a willingness to consider programs like guaranteed income.

Davis, of the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, said programs like universal basic income would be effective in reducing community gun violence.

“There are very targeted investments in interrupting cycles of violence and leveraging community organizations that are already working with individuals who are at highest risk for violence,” he said.

“Addressing concentrated poverty is a great way to reduce the risk factors that fuel violence.”